Coastal Rainbow Trout – a beautiful fish

| |||

| |||

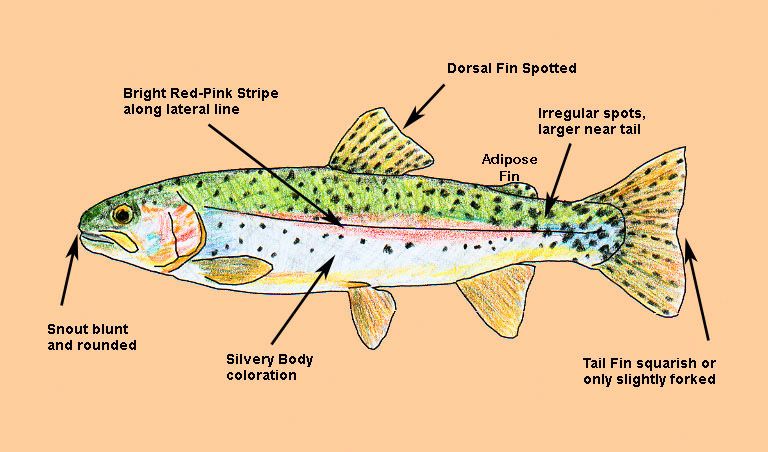

The Coastal Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus), is one of the most recognized and beautiful game fish in the world. The rainbow’s characteristics are highly variable throughout its range and between the many unique races. The species contains the Redbands, the Goldens, the Kamloops, Eagle Lake, Kern River, and the Coastal subspecies. The Shasta-strain and McCloud-strain of rainbows are considered to be from the Coastal Rainbow species. Coastal rainbow trout and steelhead are classified as the same species and differ primarily in behavior. Rainbows usually spawn in the spring, although environmental conditions may change this timing. Spawning occurs in cool water with adequate flow and streambed gravel. When an appropriate site has been found, the female digs out a depression, or redd, in the gravel with her tail fin. The female extrudes her eggs into the redd as the male fertilizes them. Hundreds, or thousands, of eggs can be deposited in one, or more redd. The female then lightly covers the eggs with gravel. Incubation lasts for a variable amount of time, depending on conditions such as water temperature and dissolved oxygen content. After hatching, the newly emerged rainbows, called alevin, spend some time absorbing their attached yolk sac and adjusting to their new free-swimming life. Once the yolk sac is absorbed, juvenile fish, called fry, begin to feed on a variety of aquatic, and terrestrial, insects, fish eggs, and other prey items found in the shallows. Larger rainbows may also search out prey such as mice, crawdads, other fish, and frogs. Migratory RangeRainbow trout are native to watersheds draining into the northern Pacific Ocean. This range extends from northern Mexico to western Alaska and across the Bering Sea to eastern Asia. This world-renowned gamefish has been transplanted to streams all over the world. Anglers can now fish for rainbows in the rivers and lakes of New Zealand, South Africa, Nepal, South America, Hawaii, Australia, Europe, and Central America. Natural barriers kept Rainbow Trout from inhabiting most of the streams and lakes in the High Sierra. Their existence to the Sierra was limited to streams at the lower elevations only on the western slopes. Only recently, though trout plantings, have the Coastal Rainbows extended their range to Sierran waters above 4000 feet elevation. The excellent fighting ability, and beauty, of the rainbow trout has made it one of the most sought after freshwater gamefish. Once hooked, rainbows are considered one of the most acrobatic, and feisty, of all the trout species. Many different styles of angling are used to catch the rainbow, and fishing opportunities exist year round. Bait, lures, and flies are all used to catch rainbows from lakes and streams. Indicator of Watershed HealthLike all trout, the rainbow is an excellent indicator of watershed health. The current condition of rainbow trout populations is variable between watersheds and races. Many factors have contributed to local population declines, including human-made barriers, excessive water diversions, habitat destruction, lowered water quality, effects from hatchery fish, introduction of diseases and non-native species, genetic isolation, and over-harvesting. An interesting conservation issue involves the fragmentation of steelhead populations into ‘land-locked’ resident rainbow trout. It is known that the offspring of certain rainbow trout populations within coastal watersheds have the ability become steelhead. Conversely, steelhead offspring can opt to never go to the sea and become resident rainbows. Many populations of migratory steelhead have become isolated behind human-made barrier, such as dams, and are now considered resident rainbows. It is likely that some offspring from these ‘land-locked’ populations still make it downstream passed the barriers and become steelhead, but no steelhead can get back upstream past the barrier. Unfortunately, the populations above barriers are experiencing a loss in genetic diversity due to their isolation. Valuable genetic information can leave the population, but no new information can return to it. Unfortunately, policy makers don’t manage these populations above barriers for their ‘steelhead potential’. Often these rainbows do not receive the protection steelhead get downstream, although they may be contributing to the steelhead population. In many cases, these isolated populations are free from the effects of hatchery steelhead and are the most genetically pure native stock in the watershed. All coastal rainbows should be protected as if they are steelhead, they might be someday. On the flip side, many interior races of rainbow trout have evolved because of their isolation from other migratory populations and depend on this isolation for their survival. Rainbows from other stocks, and similar species such as cutthroat trout, can interbreed with these races and endanger their unique character. Resource agencies should manage these interior races free from the effects of fish stocking. Distinguishing CharacteristicsRainbows have a sleek, streamlined shape, adipose fin, and soft-rayed dorsal fin. The rainbow can be distinguished from other salmonids by the presence of small dark spots dorsally, and on the entire caudal (tail) fin. The upper half of the body is often a dark olive or steel blue color. The rainbow often has a pinkish-red lateral stripe on the sides and similarly colored gill covers. Males are generally more colorful than females, and during spawning, often develop an elongated jaw and snout that curve in at the ends toward the mouth. The size of rainbow trout is highly variable throughout its range, between different races, and between populations that exhibit different life history behaviors. For instance, a coastal rainbow trout may grow to only 12 inches while another fish, identical in form and genetic makeup, may go to sea several times and grow to well over 40 pounds. Kamloops rainbows commonly grow to over 20 pounds, while a Kern River rainbow over 3 pounds is extremely rare. Because there is no taxonomic separation between rainbow trout and steelhead, the largest rainbow recorded was a 42 lb. 2 oz. steelhead caught in the ocean near Bell Island, Alaska. Native tribes in northern British Columbia have reportedly trapped larger fish. | |||