The Kamloops Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss kamloops) was introduced to California in June 1950. 1,000 yearlings brought in from British Columbia were released in Shasta Lake by certain sportsmen out of Redding, CA. Since then, they have been introduced within other lakes of the Sierra such as Crowley Lake. It is the largest non-migratory Rainbow Trout. Kamloops prefer stillwater lakes and will spawn within the tributaries of the lakes during the Spring. Spawning takes place when the fish are 3-4 years old. Males will fertilize the eggs at the same time the female releases them in loose gravel areas of the stream. Generally, the adults die after spawning. They can survive a large range of temperature but prefer clear, clean water. Kamloops will eat leeches, snails, crustaceans, and worms. They prefer to feed on the bottom in the weedbeds. The name of Kamloops came from the area in which they were discovered in 1812, Fort Kamloops, British Columbia, Canada Distinguishing Characteristics

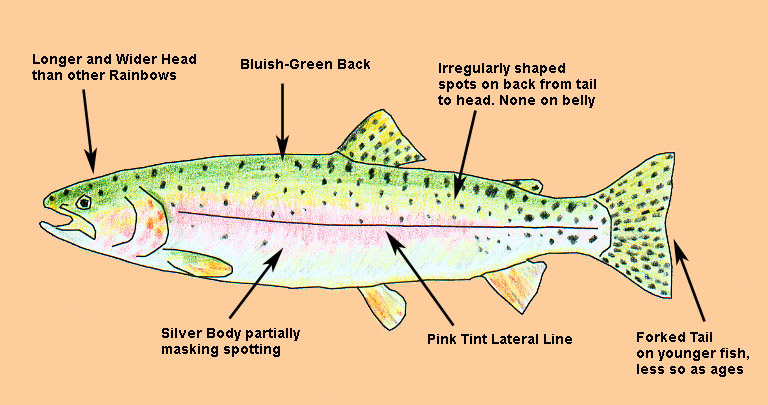

The younger Kamloops can be recognized by a distinctly forked tail. This trait becomes less evident as the fish ages. They have small v-shaped spots over their body except the belly and the head. A few round spots might be seen at the top of the head and behind the eyes. The body is generally silver with a bluish or green tinge on the back and silvery sides and belly. The body type is generally streamlined. The heads are longer and wider than other types of Rainbows. Kamloops Trout

by Ron Newman

Is there really a “Kamloops Trout”? A trout that is distinct and different from other Rainbow Trout? Surprisingly the answer is both yes and no. Since this seems a contradictory answer, it will require a quick look into the history of the Kamloops Trout to discover why.

Fort Kamloops was established in 1812. Soon, the early residents had time to try some angling in the local lakes. Virtually all the smaller upland lakes were barren and only the larger mainstream lakes had resident fish.

Over the next 80 years, stories began to be whispered about the trout being caught in the southern interior of British Columbia. These stories grew and told about a trout that had more stamina and strength than other Rainbow Trout and grew to a very large size. It also looked somewhat different than the familiar Rainbows.

Finally in 1892, samples of this fish were sent to a Dr. Jordan at Stanford University. This was before the days of refrigeration and rapid transit so I expect the fish arrived somewhat ripe. However, Dr. Jordan went about the smelly task of identifying the fish and found that indeed the fish were physically different from the Rainbow Trout scientifically named Salmo gairdneri at that time (they are now named Oncorhynchus mykiss).

These western Canadian fish averaged 150 to 154 rows of scales. That was significantly higher than the scale rows of Salmo gairdneri. It also had fewer gill rakers (those finger-like projections on the inside of the gills which filter out debris), fewer rays or bones in the dorsal and anal fins, and fewer branchiostegal rays (those indented lines under each of the jaws).

Proportionally, the head of these trout was wider and longer than Salmo gairdneri. The maxillary process and the length of the fins were also longer. The underside fins were a brighter orange, more like a Brook Trout, and the camouflage spots were more distinct than on other Rainbow Trout.

Armed with these physical differences and the stories of their stamina, strength, and size, Dr. Jordan believed he had a new species of trout. He gave it the scientific name Salmo kamloops or Kamloops Trout. With an official name, the legend of the Kamloops Trout had begun.

Over the next 30 years, a couple of small fish hatcheries were established, some of the smaller lakes were stocked with Kamloops Trout and a commercial fishery was even started on the larger lakes in the area. Lakes such as Kamloops, Kootenay and Shuswap Lakes were producing fish that averaged about ten pounds. And there were stories of fish from 30 to 55 pounds, such as the big one from Jewel Lake. Fly fishers started to fish the newly stocked but smaller lakes. Kamloops Trout of 15 to 18 pounds were being caught from lakes after the third year of stocking. Salmo kamloops was becoming known to wealthy anglers around the world.

Then in 1931 a Dr. Mottley began to study the Kamloops Trout. He discovered that the differences in Salmo Gairdneri and Salmo Kamloops were due to environmental conditions rather than genetic differences. He had found that the spawning streams in south central British Columbia were about 9 degrees Fahrenheit cooler than most spawning streams around the world.

He conducted an experiment in which Kamloops Trout eggs from the same fish were hatched and raised in two different environments. One set of eggs were hatched and raised at the normal stream temperatures around Kamloops and the second set were hatched and raised in waters 9 degrees warmer than would normally be expected in the local spawning streams. Those fish raised in the warmer water did not develop the extra scale rows and other physical differences of Salmo Kamloops. He had raised both types of fish from the same batch of eggs and thus proven that Salmo Gairdneri and Salmo Kamloops were indeed the same fish. The differences were environmental rather than genetic.

In subsequent work, Dr. Mottley also found a few other quirks of the Kamloops Trout that are of interest to the angler. The cool spring time and hot summers played a part in the development of these fish. Water temperatures remained cool, like alpine streams, during the critical phases of development, which are the egg, alevin and fry. This cool water was responsible for the physical differences in the fish. During the hot summer the water warmed sufficiently to provide vast quantities of food for the growing trout. This helped to explain the strength, stamina and size differences. Mottley even found that the physical characteristics of the Kamloops Trout changed with the elevation of the lake in which they were raised. Also, attempts to stock Kamloops Trout in other locations have all met with failure unless the environmental conditions are virtually the same as in southern British Columbia.

Shortly after Dr. Mottleys work was confirmed the scientific community removed Salmo Kamloops from its official registry of fish species. Officially the Kamloops Trout ceased to exist. And yet those fish with that extra strength and stamina, those extra rows of scales, the fin and camouflage spot differences and larger size are still in the lakes of south central British Columbia. So in answer to our original question, “YES” there is a Kamloops Trout that is distinct and different from other Rainbow Trout in terms of its fighting ability and physical characteristics. But “NO” it is not genetically different from the more familiar Rainbow Trout. It is a product of the local environment and cannot be exported.

As a final note to avoid any misunderstanding for those who may be coming to British Columbia to fish Kamloops Trout for the first time. These trout no longer average 10 pounds. Kamloops Trout in the five to 10 pound range are still caught but over the years most of our lakes have been over stocked at one time or another. This has significantly reduced the amount of available food in the lakes and thus reduced the average size and fast growth rates of the Kamloops Trout. In addition, some lakes that have historically been prime producers of large Kamloops Trout are now classified as “Put-And-Take” lakes and are still being over stocked.

Today you can expect about one fish in a hundred to be five pounds or over (depending on lake, etc) and another 23% of your catch should be in the two to five pound range. A two pound fish will average about 18 inches in length.

|