Little Kern Golden Trout

| |||

| |||

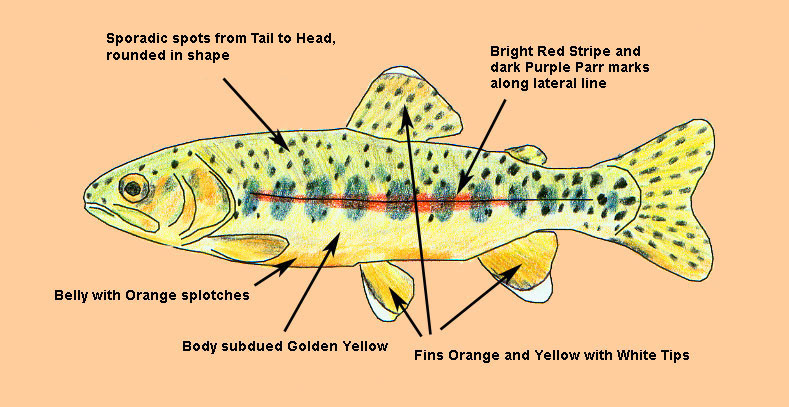

The Little Kern Golden trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss whitei ), is native to high elevation streams and lakes in the Little Kern River, a major tributary to the Kern River in the southern Sierra Nevada. In the early 1900’s anglers and the Department of Fish and Game, eager to improve fishing, unwittingly threatened the Little Kern golden trout when they moved non-native rainbow, brown, and brook trout to golden trout habitat. The introduced fish hybridized with the goldens, making an offspring that was not a pure golden trout. This “genetic contamination” threatened the continued existence of the Little Kern golden trout. Habitat Degradation Cattle grazing in the high country impacted the fish as well – as cattle trampled stream banks – soil erosion clogged the streams, and vegetation that provided food, shade, and cover for aquatic life disappeared. By the 1970’s, the Little Kern golden trout occupied only about 10% of its original habitat, and only a few thousand golden trout still existed. The California Department of Fish and Game stopped planting non-native rainbow trout, and removed introduced fish from the Kern drainage to make room for the pure native Little Kern golden trout. Stream habitat was recovered little by little every year. Biologists removed non-native fish with an organic, biodegradable fish poison, constructed impassable barriers to prevent non-goldens from moving back, then restocked the waters with Little Kern Goldens. By 1990, after almost 20 years of conservation efforts, the Little Kern golden trout has been restored to about 60% of its range in the drainage. The Little Kern golden trout is still found only in the Little Kern River drainage, inhabiting about 80 miles of stream. Distinguishing Characteristics:The Little Kern Golden closely resembles the Volcano Creek Golden except that it has many more spots over the back and onto the head. The body is a more subdued golden yellow with a copper or brassy back. White tips exist on the pelvic, anal, and dorsal fins. Just in front of the tail, the spots are larger and rounded.

Article by Daniel P. Christenson in Outdoor California:July/August 1994DFG biologists Daniel P. Christenson and Stan Stephens were the principal managers of the Little Kern River golden trout recovery program. The Little Kern River is a western tributary of the Kern River, lying at 6,000-10,000 feet of elevation, primarily in the Sequoia National Forest and Sequoia National Park in eastern Tulare County. There are about 100 miles of stream suitable for trout and 11 small lakes in this drainage. Most Little Kern tributaries flow about one cubic foot per second after the heavy winter snow-pack has melted, with a total of about 25 cubic feet per second for the drainage. The Little Kern golden trout originally occupied most of this drainage and was found nowhere else on earth. According to old records, transplanting of Little Kern golden trout to nearby waters, including the South Fork Kaweah River to the west, began before the turn of the century. Only one of these transplanted populations is known to exist in its pure state. This population is in Coyote Creek, another tributary of the Kern River (to the east of the Little Kern) in Sequoia National Park. It has played an important part in the recovery of the species. Barton Warren Evermann, a biologist with the U. S. Bureau of Fisheries, “discovered” the Little Kern golden trout in the South Fork Kaweah River, in some Little Kern River drainage locations and in Coyote Creek while on a wilderness scientific expedition in 1904. He recognized the distinctiveness of this species and was concerned about its protection. About 20 years later, as increasingly greater numbers of people came to the Little Kern drainage, some anglers thought certain populations were being “fished out” and recommended that additional trout be planted. For the next couple of decades, the state provided hatchery trout (rainbows, brooks and browns) to sportsmen’s groups and individuals for replenishing the streams and lakes in the Little Kern drainage. Some of these non-native trout established populations and hybridized or competed with the native Little Kern golden trout. William Dill. a fisheries biologist with the California Department of Fish and Game. surveyed some of the streams and lakes in the Little Kern drainage in 1940 and 1945. He found the over harvest claims to be invalid, but recognized the threat to native golden trout from competition with brook trout and hybridization with non-native rainbow trout. He recommended against further introduction of non-native fish in order to reduce the possibility that the native golden trout would become extinct. At that time, he was not certain that any pure Little Kern golden trout remained. About 10 years later, the introduction of non-native fish was finally stopped. In 1965, Fish and Game became interested in the fate of the Little Kern golden trout. With Evermann’s original descriptions, a survey began to find if remnants of the species existed. Trout in the headwaters of several isolated tributaries were examined. A population was located in the uppermost one mile section of Soda Spring Creek in Sequoia National Park which closely fit Evermann’s original description. In other streams, DFG fishery biologists found trout which appeared to be hybridized with rainbows. Based on the presumed purity of the trout in upper Soda Spring Creek, the DFG prepared a plan to develop an artificial barrier near the mouth of that stream and expand the pure population to the balance of its drainage. By 1971, in coordination with Sequoia National Forest and Sequoia National Park biologists. Fish and Game used explosives to modify a bedrock stream section near the mouth of Soda Spring Creek. This prevented the upstream migration of trout from below and was the first step in the process to eradicate non-native fish from the drainage. Thus began the process which has led to the recovery of the species, which is very close to realization. Several attempts to genetically test Little Kern trout populations yielded little or no new insights into their status. In 1973, Fish and Game contracted with Graham A. E. Gall of the University of California at Davis to tackle the problem. In his laboratory, researchers analyzed physical characteristics, chromosome counts and electrophoretic separation of tissue proteins (gene products) of samples collected from Little Kern golden trout. The latter technique proved to be the most valuable tool in defining genetic characteristics. Interestingly, the chromosome studies indicated varying numbers occurring in trout within an individual population, a presumed genetic impossibility, which demonstrated the “plasticity” of trout genetics and confounded geneticists. The initial electrophoretic work was done by John Gold and it demonstrated distinctive characteristics of the upper Soda Spring Creek population and their close relationship to the golden trout of the South Fork Kern River. This verified Evermann’s discovery, confirmed earlier visual observations and inspired greater confidence that researchers were on he right track. Further genetic testing of more than 30 isolated populations in the Little Kern drainage resolved the issue of which populations were pure Little Kern golden trout. Final results indicated pure golden trout still existed in upper Soda Spring Creek, Deadman Creek, lower Wet Meadows Creek, Willow Creek drainage, Fish Creek and Coyote Creek. This included a total of merely 10 miles of stream with only a few thousand Little Kern golden trout remaining. It was determined that populations in the balance of the drainage had been influenced by non-native trout. At this point, natural disasters or illegal introductions of non-native trout in any of these streams would have further reduced the remaining populations or caused extinction of the species. Along with the initiation of genetic studies in 1973, there was sampling for rare species of aquatic invertebrates and a basin-wide stream survey. No other species of concern, other than the other native fishes, were identified during this process. The stream surveys identified natural barrier locations and defined the scope of the recovery project. Initial experimental chemical treatments were conducted in 1975 and 1976 by the DFG at lower Deadman Creek, upper and lower Bullfrog Lakes and the upper Little Kern River, where non-pure populations existed. These treatments verified that the target species (non-native trout) could be eliminated without any long term effects on the other natural resources of the area. Fish and Game recognized the Little Kern golden trout was threatened primarily because of loss of genetic integrity due to breeding with introduced non-native rainbow trout. This species has been a subject of Fish and Game’s Threatened Salmonid Committee since its inception in 1972. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service officially listed the Little Kern golden trout as a threatened species in 1978 and designated its critical habitat as the entire Little Kern River drainage above a barrier about one mile downstream from its lowermost tributary, Trout Meadow Creek. In that same year, almost all of the critical habitat was designated as part of the Golden Trout Wilderness. In 1978, in cooperation with Sequoia National Forest, Sequoia National Park and the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, “The Little Kern Golden Trout Fishery Management Plan” (revised in 1984) laid out a strategy for recovery of the species. Sequoia National Forest biologist Richard Standage prepared an environmental analysis report for the plan which was approved by the USFWS in 1983. Under the authority of these documents, restoration efforts began in 1979. Restoration was to proceed by piecemeal reclamation of lakes and stream sections isolated by barriers (sometimes artificially developed) at a slow and methodical pace so that no large portion of the drainage would be without fish at any one time. No more stream mileage was chemically treated than could be transplanted without jeopardizing remaining native donor stocks. Each of the remaining pure stocks was to be protected by establishing one or more additional isolated populations and the maximum genetic diversity was developed in the lower reaches where all stocks would be allowed to mix freely. Each year, proposed project activities are reviewed by the agencies involved. Public notification of planned activities, including time and location of chemical treatments, is provided periodically through the season to concerned individuals and the media. A leaflet is also prepared to inform wilderness users of proposed activities in the areas they may be visiting. Local posting of trails is done to notify travelers of the dates and location of chemical treatments. An annual report of restoration activities is prepared for distribution to those interested in the project. Before chemical treatments are conducted, visual and fly rod fish population inventories are made to provide baseline estimates so that it can be determined when a restored population has been fully recovered. When feasible, non-native trout in stream sections to be treated are salvaged by electrofishing and transplanted to non-recovered stream sections to augment recreational fishing. While this effort has little biological benefit, it does make it possible for these trout to make a contribution to fishing recreation. Stream distance flagging, stream flow determination, downstream chemical travel time estimates and volume measurements help to facilitate treatments and control the amounts of chemical applied. Live-net test fish are placed at strategic locations to monitor the progress and effectiveness of the toxicants. Lake treatments are done using an inflatable boat to apply enough chemical to the surface to treat the water. The chemical of choice was initially antimycin because of its effectiveness and rapid break down. Unfortunately, antimycin is no longer available for use. Rotenone is currently used in the chemical treatment process. Rotenone is a naturally produced, biodegradable product obtained from the tropical cube root. In the concentrations used, it is not harmful to plants, birds or mammals, including humans. Detoxification is by dilution and oxidation, or application of potassium permanganate. Live-net tests show when the water is non-toxic so that the lake or stream can be restocked with Little Kern golden trout. Restocking can be done by backpack, horse, llama, airplane or helicopter. Stream treatments are done by placing five-gallon drip cans, usually at 400 meter intervals, for rotenone with timed releases of 1-8 hours to provide a continuous block of toxic water moving downstream. Backwaters and side pools are sprayed by hand in conjunction with the stream treatment. To verify the effectiveness of a treatment, it is repeated to ensure that no fish remain. If time allows, or if there is a possibility of eggs incubating in the gravels where they may survive the treatment, a period of several weeks or months is allowed before the final treatment. Detoxification can be done by dilution downstream or from a tributary or by the application of potassium permanganate at the lower end of the section. Restocking with Little Kern golden trout can take place within a day or two after the treatment as the chemical is rapidly diluted and flushed from the section. Periodic inventories of a restored population are done to monitor its recovery rate. In 1982, the Fish and Game began an experimental effort to artificially propagate Little Kern golden trout to provide more fish to restock reclaimed waters. This has developed into a temporary golden trout hatchery at Fish and Game’s Kern River Planting Base near Kernville, which now produces several thousand golden trout fingerlings each year. Stocking of these fish, along with those transplanted from native and restored pure populations has resulted in this threatened species’ restoration to over 70 percent of its critical habitat. Complete restoration is expected in 1995. It is anticipated the Fish and Wildlife Service endangered species status delisting process could begin soon thereafter. * *The Little Kern Golden continues to be placed upon the Threatened list since the remaining population is derived from a very small population with a low genetic diversity. This low genetic diversity can impact the species in dealing with habitat change and disease. | |||